Intestinal Microbiota & Animal Performance

What is Microbiota?

Microbiota is defined by Sekirov as a term defining a set of commensal, auto-chthonic microorganisms, co-existing with a host without causing any harm. Freter defined intestinal microbiota as the usually complex mixture of bacterial populations that colonize a given area of the gastrointestinal tract in individual human or animal hosts that have not been affected by medical or experimental intervention or disease.

Importance of Microbiota:

In the recent market, the success of the broiler industry worldwide relies on the effectiveness of feed conversion. As feed is the major component of production cost (up to 70%) in broiler production,10 poor feed efficiency translates into large economic losses. In addition, costs associated with morbidity and mortality, decreased weight gain, increased time to slaughter, condemnations at slaughter, and preventative and treatment costs associated with diseases contribute to economic losses. Subclinical forms of enteric diseases make accurate diagnoses a challenge.

Intestinal Microbiota Composition:

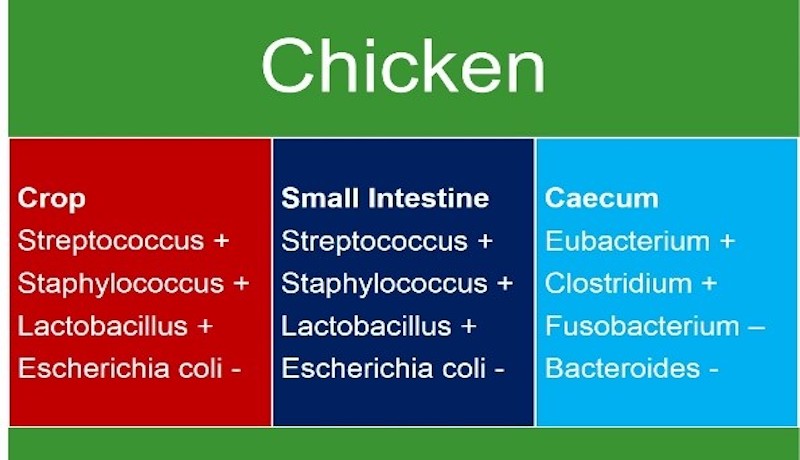

The alimentary tract of the healthy chick is considered free from micro-organisms at hatch. Following the hatch, microbial colonization of the digestive tract evolves very rapidly. The microbiota becomes fully developed when birds are close to 40 days of age. The bacteria present in the microbiota can be categorized as commensal or pathogenic. The bacterial population is very diverse comprising of over 900 species. Firmicutes accounted for 70% of the bacterial sequences, followed by Bacteriodetes (12.3%), Proteobacteria (9.3%), and unclassified sequences (5.3%). The presence of bacterial pathogens within chicken microbiota is an important issue for both chicken (E. coli and Clostridium) and human health (Salmonella and Campylobacter). The bacterial population can be affected by a range of factors, such as host, litter management, diet, and feed additives.

Functions of Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota can be Divided into Four Major Categories:

A balanced intestinal microbial community provides a barrier against pathogen colonization and contributes to the overall health of the host. In addition, they produce metabolic substrates such as vitamins and short-chain fatty acids and stimulate the immune system.

Functions of Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota can be divided into four major categories:

– Improving host nutrition

– Reducing intestinal pathogens

– Improving intestinal morphology

– Improving immunity

Improving host nutrition:

The chicken gut microbiota produces enzymes enabling the depolymerization of dietary polysaccharides. These enzymes are critical to host nutrition because chickens lack the genes for enzymes that are necessary to facilitate this process. During the depolymerization of dietary polysaccharides, gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Common SCFAs produced are acetate followed by propionate and butyrate. Butyrate or butyric acid is the primary energy source of colonic epithelia and has been shown to be essential to the homeostasis of colonocytes and the development of gut villus morphology. Butyric acid has been shown to improve growth performance and carcass quality characteristics in chickens.9 In addition, it is reported that SCFAs can regulate intestinal blood flow, stimulate enterocyte growth and proliferation, regulate mucin production, and affect intestinal immune responses.

The gut microbiota also contributes to nitrogen metabolism. The microbial metabolism of dietary protein that escaped host metabolism earlier in the gut provides further amino acids for egg production, maintenance, and growth. Gut microbiota of poultry may also serve as a vitamin (especially B vitamins) supplier to its host. Similar to bacterial proteins, most of the vitamins synthesized by gut bacteria are excreted in the feces because they cannot be absorbed by the cecum. However, coprophagic birds may benefit from bacterial vitamin synthesis.

Reducing intestinal pathogens:

The gastrointestinal tract of a newly hatched chick is void of micro-organisms but is colonized afterward by microorganisms present in the surrounding environment i.e. during transit to the farms and in the farms. This opportunity is utilized by the enteric pathogens in the environment as an opportunity to attach to and breach the intestinal mucosal layer and cause infection in new hatchlings as a result of the absence of normal gut microbiota. This is one of the reasons why newly hatched chicks are very much susceptible to enteric infections such as necrotic enteritis.

The chicken gut maintains a fine balance of its microbiota. Any disturbance to the important species can lead to the dramatic proliferation of pathogenic microbes like Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and Clostridium perfringens.

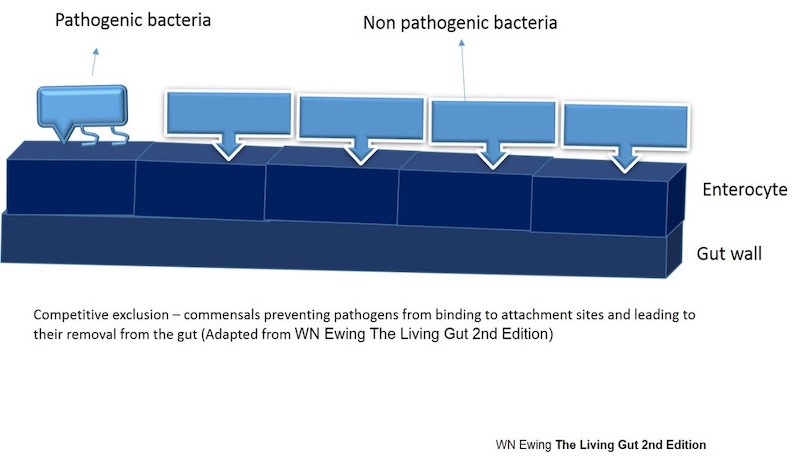

The pre-establishment of the microbiota and the maintenance of the same prior to infection is important in maintaining chicken gut health. Also the commensals, by occupying along the GI tract, this layer of dense and complex microbial communities can effectively block the attachment and subsequent colonization by most invading enteric pathogens. This phenomenon is called “Competitive Exclusion”. Some commensal probiotics like Bacillus subtilis also act by producing secondary antibacterial substances called surfactants as an antimicrobial compound to control pathogens’ growth.

Improving intestinal morphology:

Gut microbiota plays an important role in intestinal development. Studies in gnotobiotic chickens indicated that, compared with conventional birds, the small intestine and cecum of GF birds had reduced weight and a thinner wall. It has been suggested that SCFAs produced by intestinal microbiota increased enterocyte growth and proliferation. Gut microbiota also affects the intestinal morphology of poultry. Intestinal villi are shorter and the crypts are shallower in gnotobiotic birds or birds colonized with a low load of bacteria than in conventionally-raised birds.

Probiotic species (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bacillus subtilis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and prebiotics (e.g., fructooligosaccharide and mannan-oligosaccharide) increased villus height in duodenum and villus height-to-crypt depth ratio in the intestine of chicken.6 Pathogens can also change intestinal morphology. For instance, chickens with Eimeria spp/C. perfringens-induced necrotic enteritis had significantly reduced villus heights and villus height-to-crypt depth ratio.

Improving immunity:

Immune function in the gut is important as it has the largest surface area in the body and is continually exposed to pathogenic organisms and harmful substances. The gut has evolved to carry out two apparently confounding tasks: nutrient absorption and pathogen defense. The intestinal immune system consists of a robust mucosal layer, tightly interconnected intestinal epithelial cells, secreted soluble immunoglobulin A, and antimicrobial peptides. The mucosal layer consists of an outer loose layer in which microorganisms can colonize and an inner compact layer that repels most bacteria. As a component of the intestinal mucosal innate immune system, the mucus layer prevents gut microorganisms from penetrating into the intestinal epithelium and serves as the first line of defense against infection. A beneficial microbial community plays a key role in maintaining normal physiological homeostasis, modulating the host immune system, and influencing organ development and host metabolism.